Fire created unknowns, many are hopeful new data will benefit San Joaquin River management

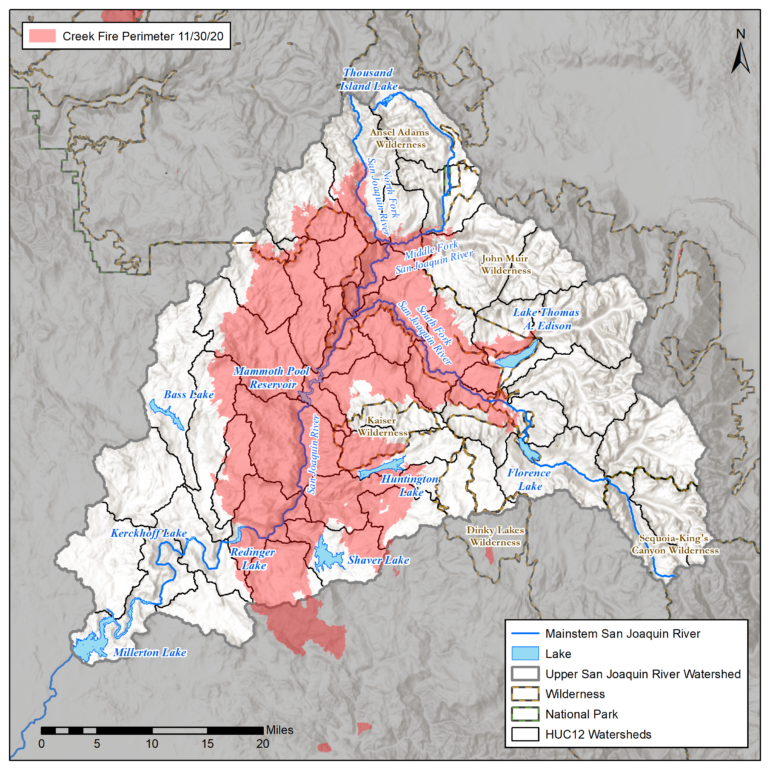

After a record-setting season of catastrophic wildfires in California, no single fire in 2020 burned more than the Creek Fire in the Upper San Joaquin River watershed east of Fresno. The Creek Fire, the largest single-source fire in California history, ravaged nearly 380,000 acres from September to November. Now, with 35% of the watershed burned, hydrologists want to better understand what impact the Creek Fire may have on spring runoff – essential to the San Joaquin Valley’s water supply and to the welfare of a burgeoning salmon population.

“Spring-run Chinook’s success is highly dependent on our ability to accurately manage river flows and regulate water temperatures,” said Chad Moore, Flows Coordinator for the San Joaquin River Restoration Program (Program), the multi-agency effort to restore spring-run Chinook to the river. In 2019, spring-run Chinook salmon were observed returning to the San Joaquin River for the first time in over 60 years, and scientists want to make sure the fish are given the flows they need in order to survive.

Moore said, as part of its effort to restore 150 miles of the San Joaquin River from Friant Dam to the mouth of the Merced River, the Program pays close attention to hydrologic runoff since it feeds the river flows that benefit the recently returning Chinook. To help predict how much water will come down to the valley from the mountains and when, the Program uses California Department of Water Resources (DWR) forecasts combined with National Weather Service forecasts to develop its own runoff forecasting process and model. But the Creek Fire has created uncertainties about how well any of those models may predict runoff for 2021.

“You’ve lost brush, you’ve lost canopy, and the soils have drastically changed as a result of the fire,” said David Rizzardo, the California Department of Water Resource’s (DWR) branch chief for hydrology and forecasting. “All of this impacts our modeling efforts,” he said.

Until recently, physical snow surveys and automated snow monitoring equipment (often referred to as “snow pillows”) were the primary data sources for capturing snow volume and density. That information, as well as other data, is fed into models to predict spring runoff (and, consequently, water supply). Much of the information is shared and paid for through a coalition of state and federal entities known as the California Cooperative Snow Survey Program, established by the State Water Code in 1929 and managed by DWR.

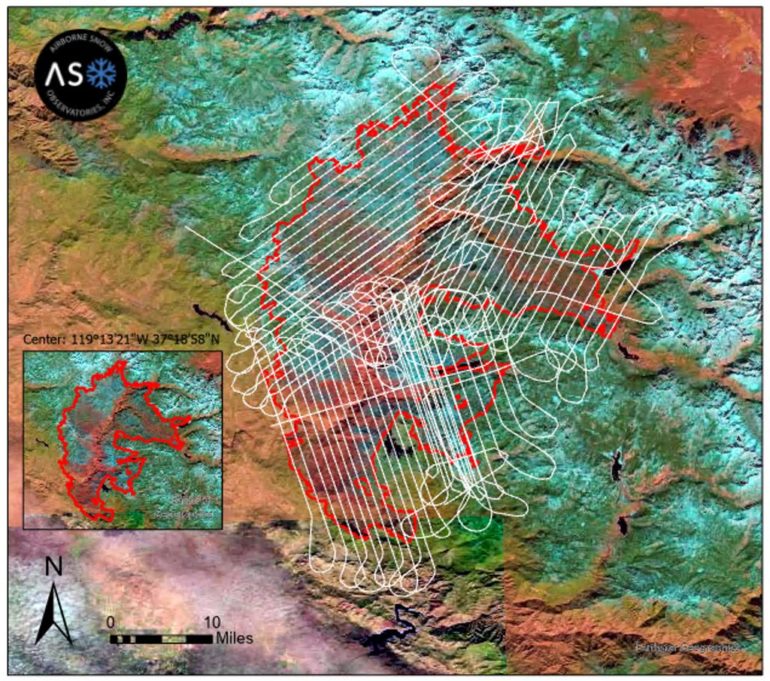

Building on that partnership, in 2017, the Program, the Friant Water Authority and the South Valley Water Association (both of which receive water from the river and are signatories to the San Joaquin River Settlement), and DWR, partnered and hired the Airborne Snow Observatory (ASO) to conduct hi-tech LiDAR (Light Detection and Ranging) imaging flights over the Upper San Joaquin River watershed. The flights are flown pre-snow to create a baseline and then during the winter in order to measure snowpack by bouncing lasers off the bare ground or snow surface and collecting the returned data. The result is a picture of surface topography, everything from fallen and standing trees, to rocks, ground cover and snow.

“The ASO flights really provide a data set unparalleled in providing a hydrologic snapshot of the basin,” said DWR’s Rizzardo which oversees most of the ASO surveys in California.

The ASO program was developed through the National Aeronautic and Space Administration (NASA), Jet Propulsion Laboratory, and the first flights were conducted by them. The most recent flights were flown by Airborne Snow Observatories, Inc., a spin-off of the NASA effort, and funded by DWR at a cost of about $225,000 for the bare earth survey. The flights are recorded at two topographical data points per meter – far greater detail than what was available pre-LiDAR. This information is particularly important now in order to give an accurate look at the watershed after the Creek Fire.

“What we gain from the flights greatly affects our ability to map the watershed snowpack accurately,” said Dr. Thomas Painter, Chief Executive Officer of Airborne Snow Observatories, Inc. (and founder of the NASA program) which conducted the recent flights. “We need to know which trees are still standing as that biomass makes a huge difference in snow accumulation and melt rates,” he said.

Typically, ASO baseline “snow-off” flights wouldn’t be necessary year after year because the land topography doesn’t change that quickly. Except, in the case of a natural disaster like a fire.

So, to bring the ASO snow-off baseline into the post-fire reality, ASO flights were rapidly arranged in mid-November to try and beat the weather for a bare ground reading. But, as it turns out, the fire didn’t just change the topography, it limited access to data as well. DWR lost a critical snow sensor at Green Mountain (see photo) where it was burned to the ground. Others sensors were also damaged and DWR is uncertain how safe it may be for ground survey crews to access some of their wintertime measuring points.

“These flights are particularly important this year as the fire limits the accuracy of some forecasting tools,” said Ian Buck-Macleod, Water Resources Manager with Friant Water Authority. “These snow-off surveys really have a multi-agency benefit for understanding risks to health and safety, debris flows, tree mortality and other factors,” said Buck-Macleod.

What all of this data will show has yet to be seen, but there are some predictions about the impact the fires may have on this winter’s runoff.

“If you lose the forest canopy and vegetation, you get a greater accumulation of snow,” said the ASO’s Painter. “But if you have that much less tree canopy to block the sun and stagger the snowmelt, and you combine the fire’s charred mass and soot in the snow over a large area which can increase melt rates, the flood potential is real.”

A change in snowpack and runoff may make it more challenging to regulate the river flows that benefit spring-run Chinook in the San Joaquin River. If runoff in the spring comes faster, because of less shade for the snow or other factors, it may challenge the ability of water managers to save those cold water flows until later in the season when the salmon need them the most. The expectation is that more ASO flights this season will continue to provide hydrologists with the data they need to predict San Joaquin River watershed runoff and optimize the state’s precious water.

“Right now, these flights may be our best look at what’s to come for the river in the spring,” said the Program’s Moore.

For more information about this story or about the San Joaquin River Restoration Program, please contact Josh Newcom at 916-978-5508 or by email at snewcom@usbr.gov.